The Early Years: 1957-1976

by Lisa Waite Bunker

The Sonoita Valley is easy on the eyes. The beauty here is in the simplicity of tall grasses, sheltering trees and enveloping hillsides. And all that sky. In the daytime, the sky has none of the haze that people today take for granted. Sunsets render the air opalescent; an elixir one may breathe. From the gently swelling tawny hills of Sonoita to the juniper and cottonwood-studded ravines of Patagonia, these valleys seem to inspire an instantaneous recognition in visitors that this must be a sublime place to live.

In truth, life here has often been difficult. Every boom has had its bust and sustainable prosperity for the valley always seems just over the next hill. In this paper, I hope to outline the history of the Town of Patagonia and to tell the story of the development of one of its institutions, the Patagonia Public Library.

History of Patagonia

Before there were mines and cattle in the hills south of the Santa Rita mountains, there were Soba, Jipuri and Apache Indians as well as a Spanish visita (branch mission) called Los Reyes de Sonoidag. When the area was annexed to the United States’ Territory of New Mexico through the 1853 Gadsden Purchase, mines (mostly lead and silver) and ranches were staked and military camps commissioned to protect the new settlers from Apache incursions. Fort Buchanan was established in 1856 and was active until the solders were withdrawn in 1861 to fight in the Civil War. Fort Crittenden (1867-1873) and Fort Huachuca (1877 to present) served the area after the war. Sizeable settlements would not develop, however, until after the coming of the railroad in the mid-1880s.

In the wake of the severe 1891-93 drought, Civil War veteran, oil tycoon and rancher Rollin Rice Richardson decided to begin investing in lead and silver mines in the Santa Rita and Patagonia Mountains. In 1893, Richardson also began to commercially develop a portion of his 144,000-acre ranch where the newly constructed New Mexico & Arizona Railroad (a subsidiary of the Santa Fe system) tracks crossed Sonoita Creek. He named the town “Rollin;” however 3 years later, when the town petitioned the United States Post Office for mail delivery, the townspeople overruled Richardson and stated the town’s name as “Patagonia” after the nearby mountains. This rebuff aside, Richardson pretty much ran the town until his death in 1923. By 1900, Patagonia’s prosperity rated a two-story railroad depot, as it was the shipping center for most of the surrounding mines. And in that year, the census counted 133 townspeople: 67% Hispanic and 32% Anglo.

By the beginning of World War One, Patagonia had running water, a wooden Opera House, three hotels, a schoolhouse, two parks and several general merchandise stores and saloons. Frank Seibold, who came to Patagonia in 1918 when he was four years old, remembers early Patagonia as a “pretty place, even then, with its long line of shade trees and in the background the cottonwood groves and Sonoita Creek….” The town was “largely a tent city with some tents made better than the rest,” with a “business district which lay on a long meandering dirt road south of the railroad. This part of Patagonia was mostly frame buildings interspersed by better constructed adobe buildings.” As one would expect, “the business district was the focal point of the town. Here everyone gathered for important events, such as the announcement of the opening of a new mine, political rallies, [and] the arrival of the daily train….” Seibold observes that “the ratio of 3 to 1, that is serious businesses to fun or leisure places, that marked most frontier towns at that time also held for Patagonia – that is – six saloons to two grocery stores, one clothing store to three cardrooms, and one church to three whorehouses.”

The town was so prosperous during the 1910s that the NM&A Railroad stopped three times a day, and when the schoolhouse burned, the voters approved a bond election for $10,000 and hired an architect from Nogales to construct a new school in the very latest mode: the mission style. I can find no mention of a public library at this time, although Doris Seibold remembers that town barber William Fessler “kept a library of comics in his shop, but only allowed men and boys to read them if they were having their hair cut.” By 1920, the population was 757 people: 58% Hispanic, 42% Anglo.

The 1920s saw uncertainty and much slower growth for Patagonia. Cattle and ore prices became unstable, and Richardson’s death in 1923 necessitated a reorganization of his real estate, mining and commercial enterprises. A new industry was brought to Patagonia in 1924 by the Zinsmeister brothers who built a ranch five miles south of town for tourists instead of cattle and called it the Circle Z. It was Patagonia’s first dude ranch.

The stock market crash in 1929 was only the second of three misfortunes that befell the town that year. That summer, unusually hard summer rains caused the Sonoita creek to flood and wash out most of the bridges east of town. By November, the railroad was petitioning for permission to abandon the line between Patagonia and Mexico. Frank Seibold provides an upbeat account of what must have been a grim time: “The economy of the town, long dependent on the mines and a few cattle shipments, now had nothing to support it…. Socializing was on the meager side. It was a time of make-do and improvisation, because full cooperation and good fellowship were the order of the day.”

Although there were CCC and WPA projects conducted in Patagonia, and a fair amount of bootlegging, the economy didn’t improve again until the late 1930s. In 1938, ASARCO built a mill and power plant at the “Flux” and “Trench” mines in the area. Those and several other mines were revived to supply the growing need for lead, copper, zinc and molybdenum by the allied armies of World War II. According to historian Douglas E. Kupel, “by the end of the war, ASARCO was shipping from 4,500 to 5,000 tons of ore monthly from the Patagonia mines.” ASARCO continued mining until 1957, thus providing Patagonia with another long period of stability. Former cowboy and longtime resident, Paul Showalter remembers how when the ore trucks came through town from the mines, the road collected a sprinkling of “fool’s gold.” Late in the day the sun would bounce off it just right: “It made it seem like the street was paved with diamonds.”

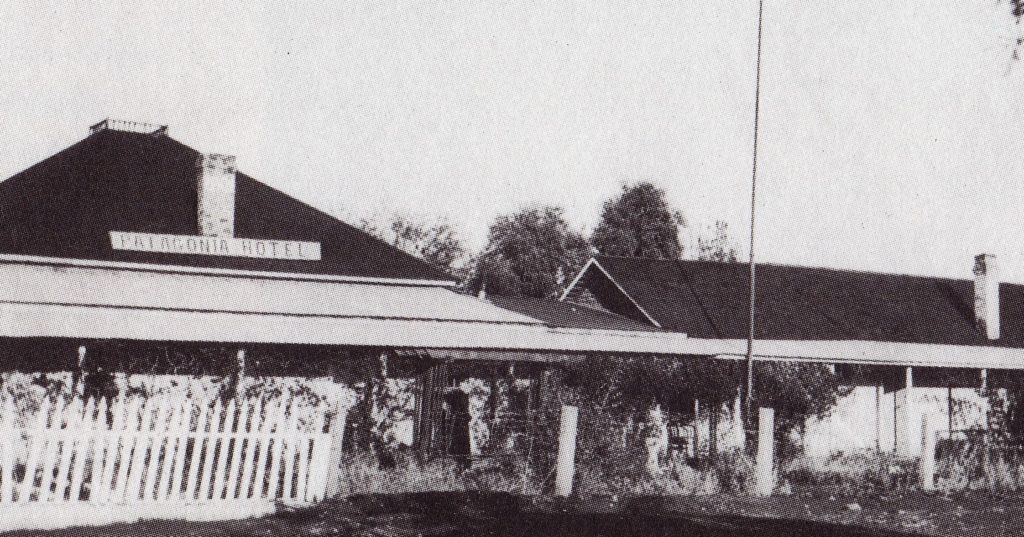

The Patagonia Hotel, now home to the Patagonia Library and Cady Hall, was constructed by pioneer John H. Cady between 1901 and 1912. In his autobiography, Arizona’s Yesterday, Cady says, “I think I may say that now the hotel is one of the best structures of its kind in the country.”

In 1947, townspeople started calling for incorporation. Proponents argued that “as a regularly organized town, Patagonia would receive approximately $10,000 a year in gasoline and sales taxes from the State. This would go a long way toward providing sidewalks and other needed improvements.” Incorporation became official on February 10, 1948. The town’s government would consist of an elected Town Council of five citizens who would then choose the Mayor from amongst themselves. The first mayor, William J. Waggoner, appointed Oliver J. Rothrock Police Magistrate, Nasib Karam Town Attorney, Robert Haverty Town Marshal and Robert Lenon as Town Clerk. Collectively, these four men served Patagonia for over seventy-five years. Publicity generated by the town fifteen years later gives an idea of the goals of these town leaders: “We have never had a Municipal Property-tax; none is contemplated. We have no outstanding bonds; no deficit – our budget is balanced! Even so our municipal affairs are managed nicely; we have paved over two miles of our streets in recent years; the appearance of the community is steadily improving.”

It was a surprise blow to the town when ASARCO closed the Trench-Flux Mill and Power Plant in 1957. Another setback (less of a surprise) came on March 13, 1962 when the Interstate Commerce Commission granted the NM&A’s petition to abandon the line between Fairbanks and Patagonia. Within a month the railroad had entirely abandoned the depot and was pulling up the tracks. Patagonia’s population by 1960 had dropped 23% to 540 in just 10 years. However, as they did during the “make-do” days of the depression, the townspeople banded together to help each other and the town. The Patagonia Women’s club formed committees to clean up the old cemetery, to weed and pick up litter in the public areas of town and to organize Dahlia-growing contests. The Rotarians led efforts to relocate and renovate the old RR depot when the widening of State Route 82 threatened the 64-year-old building. And the Town Council kept busy building the town’s infrastructure: choosing water and electricity franchises, paving the main roads (grading and oil-coating the rest), and making sure all the dogs were rabies-vaccinated and licensed. The Council heard regularly from citizens concerned about weed-choked properties, abandoned “outdoor toilets,” and livestock roaming the streets. One of the first of these civic projects, however, was the Patagonia Public Library, conceived as early as 1951 and founded in 1957 by the Patagonia Women’s Club (more on this later).

The late 1950s and early 1960s seem to have been watershed years for Patagonia, as they were for mining towns across southern Arizona. With the closure of the mines and the end of railroad service, the town’s main sources of income, indeed the original purpose for the town’s existence, were gone for good. As the townspeople looked to the future, they knew that some change was inevitable, but they also knew what they didn’t want: to become “another Tombstone,” or “another Tucson.” No ersatz gun fights or urban sprawl for them, thank you very much! Patagonians were determined to find their own way, their own solutions. Financial assistance from the state or Federal Government was sought and welcomed, but only if it didn’t seriously threaten Patagonia’s autonomy or essential character. Town Council minutes reveal how carefully Patagonia was protected from change considered to be uncomplimentary to the town’s uniqueness. Both zoning and annexation of surrounding land are repeatedly considered and rejected; to this day, the Town of Patagonia has never grown beyond the original square mile platted by Rollin Richardson in 1898.

During this time, the townspeople and council became increasingly aware of the power of publicity and of the marketability that Patagonia had as a tourist destination for those fascinated by the west. This was the heyday of the dude ranch, and the Patagonia area became a magnet for “dudes” from the world over. Photographs of the town were sent to Hollywood movie location scouts; the musical “Oklahoma” and several John Wayne movies, including “Rio Lobo,” were filmed in the area. Life Magazine photographer Bruce Davidson made several visits, and included photographs of Patagonia in an article on the “last of the unspoiled western towns.” Arizona Highways also frequently featured Patagonia in articles that enthused about the town’s quaintness and unsurpassed scenery. Retirees were also targeted with advertisements that touted Patagonia’s natural beauty, temperate climate and low tax rates; several landowners operated trailer courts on their properties.

By the end of the 1960s, four new attractions were working to bring increasing numbers of visitors to Patagonia. In 1960 heiress Ann Stradling opened the Museum of the Horse in the old Patagonia Commercial Company store building. The museum housed a unique collection of stage coaches, buggies, saddles, art and memorabilia from all over the world. The other new draws were recreation and nature-related. When the right-of-way issues with the railroad were resolved in 1966, the land where the tracks had lain in the center of town was landscaped and named Richardson Park. Then in 1968, Sonoita Creek was dammed ten miles south of town to create Patagonia Lake, initially a private resort offering camping, swimming, fishing, and boating. It was later made a state park in 1974. In 1969, the Nature Conservancy bought 312 acres of “the grove,” a section of the creek that was nesting area for hundreds of bird species, and created the Patagonia-Sonoita Creek Wildlife refuge (it is now 850 acres).

According to the 1970 census, the population of Patagonia was back up to 630. By 1980, it had burgeoned to 980 in the town alone; areas outside the city limits were growing even faster as some of the old ranches were sold and developed as subdivisions of “estate” and custom-built homes. Artists and writers were also discovering Patagonia’s charms.

However, by the early 1980s, fewer and fewer tourists were making the trip to Patagonia. The Museum of the Horse was moved to New Mexico in 1985, and the town began to experience problems caused by both internal and external forces. The town’s budget may have grown to $600,000, but a series of federal and state mandates threatened the town’s solvency. Beginning in 1988, it was discovered that the town’s sewage-treatment plant and landfill were polluting Sonoita Creek, and that the water reservoir was in dire need of renovation. Retrofitting the sewage-treatment plant alone was estimated to cost $1 million. Terry Piper-Moreno, Town Clerk and Treasurer of Patagonia described her job as part detective and part gambler as she sniffed out creative funding sources and competed for increasingly scarce federal grants and loans.

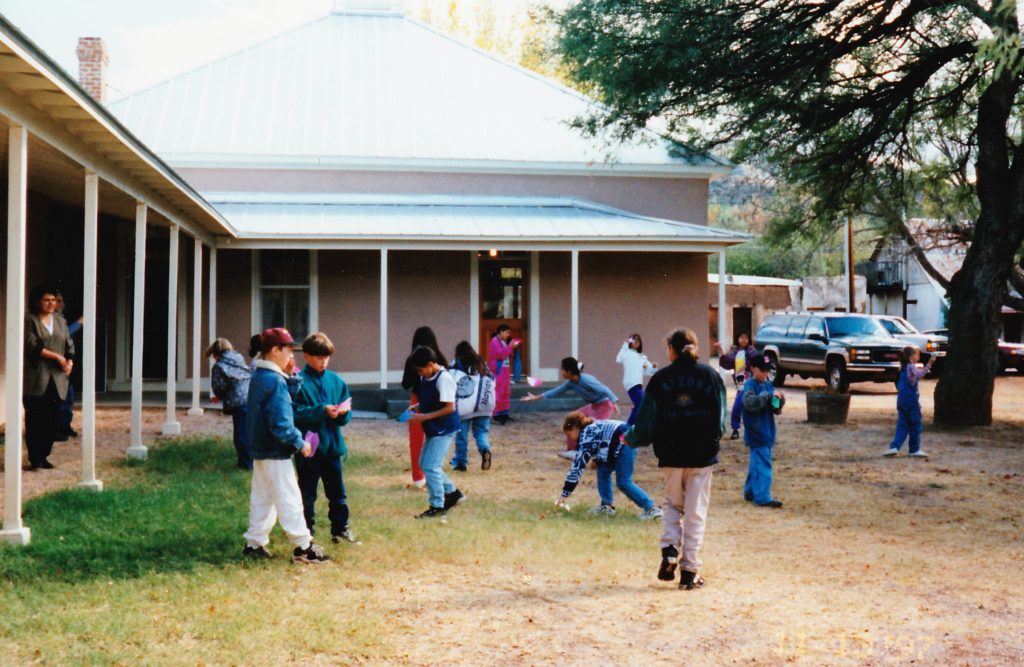

The Women’s Club and the Library also had an infrastructure problem on their hands. In 1979, surveys related to minor renovations of Cady Hall, now the oldest building in town and an official historic site, revealed the structural failure of the later (kitchen) addition. The electrical wiring was inadequate if not dangerous, the bathrooms were not handicapped accessible and the library had grown to 3 extremely crowded rooms (see Jean Rukkila’s poem at the end of this paper). Unfortunately, the Women’s Club membership had dwindled, and the venerable building’s upkeep had become a burden. When grants research revealed the fact that Cady Hall would be eligible for more kinds of monies if it was publicly owned, the Women’s Club deeded Cady Hall to the town in 1989 and an ambitious restoration project was begun. Dorothy Thomas and a committee consisting of a cross-section of townspeople and area residents envisioned a “community center as well as an enlarged public library.” Eventually it was decided to create an addition for a library reading room and to enclose the porch on the east side of the “apartments.” These changes were “desecration” to some in the town, but the work went ahead in August of 1990. The Cady Hall Restoration Committee eventually raised over $250,000 in donations and grants and the library moved into its renovated rooms in 1996. Few now deny that the new library is a sunny and inviting place to be.

But the town’s troubles continued. When the 1990 census counted nearly 100 residents fewer than 1980, it precipitated a loss of federal and state funds to the town of about $43,000 which caused a 20% cut in personnel; 9.5% was cut from the budget overall . Eventually, the census figures were revised up to 923, but not before the town levied a 3% sales tax, making it the highest in the state.

The response of the residents was to bring the visitors back by holding arts and crafts fairs and by forming the Patagonia Community Association. The purpose of the Community Association was to “pump new life into Patagonia’s ailing economy” by encouraging new businesses and supporting the existing ones. Jeffrey Cooper, the President of the Association, was also manager of the Nature Conservancy’s wildlife refuge at Sonoita Creek. Under his direction, the 70-member association made a concerted effort to attract eco-tourists and the businesses that cater to them: bed and breakfast inns, a health resort, art galleries and a back-roads touring company. Patagonia was now on the map as a birder’s paradise.

On August 9, 1993, Patagonia suspended its Town Clerk, Treasurer and Manager, Terry Piper-Moreno, for embezzlement. Piper-Moreno was a Patagonia native who began her career as Town Clerk when Robert Lenon resigned in 1984; by 1993, she was the town’s most powerful official. A routine audit revealed losses of $100,000 to $300,000 dollars beginning around 1991. Piper-Moreno was convicted in 1995 and sentenced to 5 years in prison. To make matters worse, the town did not immediately fill her position, but hired a financial consultant from Globe instead. Paul Meany was not a CPA and apparently neglected to balance the town’s checkbook. By September of 1997, the town’s paychecks were bouncing and the mayor and council had another crisis on their hands.

Mayor Shirley Treat and the Town Council responded by temporarily canceling employees’ health insurance and stopping the salary of Librarian Abbie Zeltzer along with 17 other employees. Water and sewer rates were raised 10%, and Mayor Treat suggested closing the Library altogether, calling it a “Cadillac we can no longer afford to pay the gas for.” To say this statement outraged and galvanized the town is an understatement. A wide variety of people led by the Friends of the Patagonia Public Library came together once again, this time to save the Library that they considered the “heart of the community.” I hope to do justice to the story of its founding.

Patagonia Public Library, 1951-1976

As I read Michael Harris’ 1973 article, ”The Purpose of the American Public Library: A Revisionist Interpretation of History,” I came to the conclusion that the history of the American public library could not be definitively written by studying only the libraries of large cities like Boston, New York City or Chicago. Our history is also to be found in the efforts of small to medium-sized libraries that collectively serve a much wider public. I have chosen to explore the story behind the early years of the library of Arizona’s fourth smallest city, Patagonia.

Patagonia has had several cycles of prosperity and recession since it was founded around 1898. Information uncovered so far shows that the first discussion of forming a public library occurred in 1951, but what precursors were there? Although neither Fort Buchanan (active 1856-1861), Fort Crittenden, (1867-73) nor Ft. Huachuca (1877-present) are listed in the 1876 Report, it is very likely that these installations would have had a book collection, if not a reading room available to the soldiers. According to Don Rickey, the author of Forty Miles a Day on Beans and Hay, larger western posts had libraries whose primary function was to support the continuing education of the troops. A contemporary account of Fort Laramie’s Post Library in 1870 describes it as “containing about 300 old, nearly worn out books. A number of papers and periodicals are subscribed for from the Post General Fund and kept in the library room to which the enlisted men have access.” Rickey adds that “some troops and companies had library clubs and ‘literary societies,’ to which members paid a small fee as their share in the subscription fund.” When an installation was decommissioned, books in the official library were usually carried back to the Regiment Headquarters. Social lending libraries were probably dispersed among the subscribers.

According to historian Jesse Shera, public libraries do not form “without financial resources superior to the demands of mere subsistence.” The first time one can say this about Patagonia was during the mining boom years of the 1910s and 20s; however, I have not found records of the existence of any sort of library (other than the barber shop’s comic book collection) during this period.

The Patagonia Women’s club started discussing the formation of a town library about two years after the town incorporated; Roberta Stephens Galtin remembers raising the issue after she took office as Women’s Club President in 1950. By this time, several other libraries existed in the area, but none of them satisfied Patagonia’s needs. As early as 1949 Patagonia Union High School had a library with a very small collection of classic literature and American history, but it did not provide access to the whole town. Nogales, the Santa Cruz County seat 12 miles away, had had a public library since 1943 and had been sending a bookmobile to Patagonia and the smaller communities in the area, but neither the bookmobile nor Nogales’ library were convenient to use. The road to Nogales was often in such poor condition that a trip to there and back without a flat tire was a rarity. I have little information on the bookmobile, but neither of the early residents I have spoken to remember ever using it.

The Patagonia Women’s Club solicited book donations from townspeople throughout the 1950s; the resulting gifts over the years outgrew several storage places because there was still no building chosen to house them.

In June of 1953, Patagonia resident Virginia Horrocks, the retired Post Librarian and Newspaper Editor at Fort Huachuca went directly to the Town Council and offered “her collection of 6-700 books for a nucleus for a Town Library if they can be made accessible to the entire community of Patagonia.” The Town Council voted to accept the gift, but three months later decided to ask Mrs. Horrocks if she was “willing to agree to a small charge being made.” It is not clear whether this meant a fee that Mrs. Horrocks was to pay, or the potential library users, but at any rate, she withdrew her offer the following February. Mrs. Horrocks remained active in the community: she rarely missed a Town Council meeting and from 1969 until her death in 1971, she self-published the town newspaper, The Patagonia Patriot. To my knowledge, her book collection was never offered to the city again.

One month after Mrs. Horrocks’ final decision, Mrs. Marvin Jones presented her concern to the council that “the town go ahead with the projected library” and suggested that it be housed in her store. No action was taken, and on September 1, 1954, Mrs. Jones again came before the council and “requested that a committee be appointed to take care of details and problems.” The council passed a motion stating that work should begin on a library and that council members William Wearne and William Waggoner were to be appointed to the new Library Committee. Wearne and Waggoner were authorized to spend up to $25.00 on their first duty, building shelves for the donated books still in storage.

But for the next three years, the town council appears to make no further progress on the library other than to discuss the “collection and care” of the donated books. The Women’s Club must have continued to pursue solutions, however, because in November of 1957, council minutes note that Mike Rivera and Renaldo Sanchez are to be paid $52.00 for “construction work on the Women’s Club Library.”

The Patagonia Women’s Club, now headed by Lena Des Saulles, had decided to temporarily locate the library in one room of their own “clubhouse,” the former Patagonia Hotel (built between 1900-1912 and now called Cady Hall) that they had purchased in 1947 for $3,000.00. Cady Hall is a simple adobe building, consisting of the Hotel’s former dining room and bar, a 35’ x 35’ area used as the Women’s Club meeting room and rented out for special events, and wing of eight small “apartments” abutting the east end of the hall, which had been the hotel’s sleeping quarters. A small kitchen and bathroom, both later additions, were attached to the other side. Patagonia’s old Opera House had fallen into disrepair many years earlier, so Cady Hall was (and still is) the site for many of the town’s dances, lectures, political rallies, and concerts, as well as the town voting place at election time. Rivera and Sanchez had been paid to install a door between the hall and the first apartment that was to be Patagonia’s library.

The Town of Patagonia Public Library opened in late 1957 with little fanfare and no acknowledgment by a Town Council busy dealing with the aftermath of the closure of the mines. Nadia Riggs Banta, a Women’s Club member, was its first librarian. She had volunteered to drive down from her farm near Mowry once or twice a week to administer the collection created from the “best” of the donated books, supplemented with others loaned from the Library Extension Service in Nogales. This first book collection was mostly fiction and history; afternoon hours were chosen so that school children could use the library for research. Mrs. Banta is remembered as being business-like, but accommodating and helpful.

What was Patagonia like in 1957-58? Miners, mostly Mexican-American, were unemployed; the town council attempted to provide relief, but only after writing to Fort Huachuca to ask Post officials employ those out of work. There were four churches in town: Assembly of God, St. Teresa’s Roman Catholic Church, a Seventh-Day Adventist church, and the Methodist Patagonia Community Church. Service and social groups were also popular: the Rotary Club, Commercial Club, Zonta Club, High School Board, PTA, Boy, Girl and Cub Scouts, Masons and Eastern Star, Cowbelles and Pythian sisters all flourished in addition to the Patagonia Women’s Club. Roberta Galtin, a wife with young children at this time, remembers looking at her calendar and realizing that she was busy 17 days of the month, not counting Sundays! The High School Football team’s games on Friday nights were well attended, as were the full-length tackle” Powder Puff games between the junior and senior girls. The High School also had musical and drama clubs, as well as volleyball and softball teams. The nearest movie theater was in Nogales. Troublemakers “loafed” at the Post Office and occasionally vandalized the lobby after hours. And when school children were caught throwing rocks in the cemetery one summer, the solution was to open access to the softball field at the High School. Girls could join the Future Homemakers of America and enter the “Miss Santa Cruz” beauty pageant, however, the annual Fourth of July Rodeo was probably the most popular event of the year.

In the Town election in the spring of 1958, indefatigable Women’s Club President Lena Des Saulles was elected to the Town Council, along with Bert Blabon, Ray Bergier and Abram Figueroa. One of Mrs. Des Saulles first motions was to open discussion of a mill-tax to support the library. Although Attorney Karam was instructed to find out what the amount would be, this source of funding for the library did not bear fruit. The only income I have been able to verify during these first months of the library’s existence was the $10.00 (around $700 annually, when adjusted for inflation) paid by the town to the “Library Board” monthly “as budgeted.” Unfortunately, the budgets and records from the Library Board from 1957 to 1962 are no longer extant, so I cannot tell what this money was used for, or who was on the board during this early period. Judging from the library’s subsequent funding requests, it is clear that the money was not intended as pay for Mrs. Banta, or for basic supplies like index cards or a typewriter, chairs or even new books. It is possible that this was the cost of rent for the room.

One of the problems that the library had in the early days was the Council’s (and possibly the townspeople’s) perception that the library belonged to the Women’s Club. Town officials refer to it as “the library,” or “the Women’s Club Library.” Mrs. Des Saulles repeatedly went before the Council to remind them that “while the local library is currently sponsored by the Patagonia Women’s Club to the extent of their furnishing quarters and utilities, the proper designation of the said library is ‘The Town of Patagonia Public Library.’” Mrs. Des Saulles also made sure the council was apprised of the library’s progress: “the library is open every Tuesday afternoon and gets good play.” Another day, the council is told that “the Town Library is servicing twenty-five cards per week.” This mild sort of politicking seems to have little impact; pleas for town funds to pay for supplies and clerical assistance, as well as requests for reimbursement gas money for Mrs. Banta’s trips to town are never addressed by the council.

On May 10, 1960, the Patagonia Library received its first invitation to join a proposed county-wide library system. A letter from the Santa Cruz County Board of Supervisors stated that “incorporated towns may become part of [the county] library system. The Board of Supervisors may appoint a qualified librarian and shall then levy a mill-tax, under ARS 11-192 to support same. The present extension library service is about to expire. Patagonia would qualify as headquarters for expanded service if Nogales was not interested.” Mrs. Des Saulles was appointed to contact Patagonia’s district representative William Holbrook to initiate action on joining the county system. For the last year, Attorney Karam had been trying to find out what Patagonia’s per capita share of county library money was, and this offer may have seemed to be an answer to the question of how to fund a town library. Curiously, the issue of the county-wide library system is not spoken of again for years, and two years later the town receives its first check for $200.00 ($1,065.00 when adjusted for inflation) from the county for the library’s support.

By August, many on the town council were having visions of a “civic building, to include a library and other public facilities.” Support was not unanimous, but a vote was passed to begin a fund to pay for a town hall. This project never came to pass, possibly because of the impact of the loss of the railroad and the tax base it provided.

The 1962 advent of library income from the county seems to have forced a formalization of the structure of the library’s administration. Attorney Karam pointed out at the July council meeting that according to ARS 9-411-419, the Library Board must be appointed by the local government agency (as opposed to the Women’s Club?). Eventually, the council decides to appoint Mrs. Des Saulles, Laura Bergier, Mrs. Naomi Lenon, Mrs. Nadia Banta, former mayor Mr. Eddie Loftus, and Mrs. Hilda Blabon. This new board is allowed to decide on its own terms of office. The library money is to be put into the “Library Fund,” paid into the Town Treasury and “checked out” by a double signature each time it is needed. Lena Des Saulles went on to chair the Library Board of Trustees until 1966, when her husband died.

L-R: Early Patagonia Public Library Board of Trustees members: Mrs. Seibold, Grace Baker, Mrs. Anna Fortune, Lucy Stevens, Laura Bergier, Mrs. Nadia Banta, Librarian, c. 1963. (Arizona Historical Society Collection, #63731)

Another consequence of the county money was that the library had to be an unambiguously public one in terms of its financial support. I have not confirmed this, but it appears that there may have been a requirement for the town to match the county’s amount, dollar for dollar. Starting in 1962, when I begin to have some firm records of budget amounts, the library receives identical amounts from both the county and the town governments: $200 in 1962 ($400 total, $2130 adjusted) and 300 in 1963 and 1964 ($600 total, $3200 adjusted). The county monies had to be requested anew every year, and could not be counted upon to arrive at any consistent time during the fiscal year. All the same, it made a substantial difference in the library’s ability to function. Mrs. Banta was paid $35.00 a month ($2240 annually in today’s dollars), a clerical assistant was hired (usually a High School girl), and the library hours were tripled from being open two hours on Tuesday afternoons to six hours (Mondays 2-5pm and Thursdays 3-6pm). The library was finally able to afford a typewriter; there is no indication that new books were purchased.

It was agreed with the council that any additional money the library received through donations and fund-raising could stay in the library’s petty cash and not need to be signed for. The Board of Trustees set about to raise money through the traditional women’s club methods: bake sales ($32.45 net), spaghetti dinners ($45.58) and poncho raffles. When donated books deemed “outdated” started piling up, these were also sold at the bake sales for five to ten cents each.

In early 1968 Nadia Banta stepped down as Librarian after eleven years of service. The new Librarian was a man named Howard Taylor. Very little is discernible about Mr. Taylor’s qualifications from the Library Board minutes — his first request is for a Post Office box for the library. However, the Board must have had confidence in his knowledge of books because he was allowed to make decisions about discards and was included on a book-buying trip to Tombstone with Mrs. Fortney, the Board President. Mr. Taylor was noticeably condescending toward young women (see comments below about the library assistants and high school students) and had a punitive attitude toward overdues. In November 1971, he suggested that “children with overdue books [should] have their names posted on the desk.”

During his four years as librarian, a series of different high school students are hired as assistants in the library (Margaret Laguna, Mary Helen Matrecito, Angie Soto, Emilia Benedict, Diane and Irene Tapia and Margie Patti). Most were paid through a needs-based work program called the Neighborhood Youth Corps, administered out of Nogales. It seems that as soon as one assistant was settled in to the position, the funds would be cut, or she would be found to be over the income bracket for eligibility. Every single change of personnel had to be brought before the board for discussion; occasionally, the Town Council is petitioned to pay for staffing when the NYC would or could not. The library hours continued to average 5-6 hours open each week, although this was often disrupted because of the staffing problems. Little is mentioned in the minutes about the assistants personally. One is criticized for “poor work habits,” another is praised for being punctual, “very quiet, neat & modest and [for keeping] the library and books in good shape.”

Crowding in the tiny room used by the library reached critical mass in 1970 when the board purchased a filing cabinet, a new table and eight folding chairs, so it was decided to speak to the Women’s Club about the possibility of the library’s taking over the adjoining apartment. The contact was successful. The Board received permission to expand to a second room, and was even given a subscription to National Geographic Magazine. Draperies were donated, Mrs. Fortney and her son painted both rooms, and a couple of months later, the books were placed on the shelves “in the proper alphabetical order according to author.”

With Mrs. Ethel Noble’s election as Board President in 1971, the board begins to earnestly discuss stimulating readership and usage of the library. Each member is requested to think of some ideas. Some of the suggestions that were acted upon were: to “put in Mrs. Ward’s column [in Nogales International] some interesting item about the library.” Another thought of having a “display of exceptional books in some public place to attract reader’s interest and to give the public the information that the library has so many good books.” Mrs. Ward’s article was quite short. It stated that: “For the size of our town, we have one of the nicest libraries possible,” and gave the location and the hours. The Board thought the book displays held at the Post Office (four in all) were more successful, especially at first. The Board does not appear to have consulted with other libraries or library manuals for additional outreach ideas.

Usage by high school students was also monitored; the results reveal Howard Taylor’s dismaying lack of regard for the female learner. In April 1972 it was noted that circulation was down, but “more high school pupils used the library for reading or study than has been noticed before.” The following month, however, Mr. Taylor states, that “interest by high school students [was] not too good — mostly girls.” Mrs. Noble’s response is not recorded.

Mrs. Noble was a graduate of Smith College who had recently come to Patagonia for health reasons. According to a short biography by Paul Mihalik, she had a “wide range of reading interests and [possessed] a very curious intellect.”

Fiscal year 1971-72 represents the first complete set of statistics I have located. The collection size was figured to be 3,311, of which 1,518 books were on loan from the Library Extension Service in Nogales. There were 290 borrowers (the town’s population was 630). Adult circulation for the year was 613 books and juvenile circulation was 483, for a total of 1,096 books circulated. The library hours had been increased to nine per week (MWF 1-4). However, Mr. Taylor’s annual salary was unchanged from Mrs. Banta’s: $420. The intervening years, inflation had cut its buying power from $2240 (adjusted) in 1962 to $1725 in 1971. Assistant Diane Tapia was paid $350 for the year. Overall, the Library’s budget was $1,250 ($5,130 adjusted), which represented $800 from the town and $450 from the county.

Mr. Taylor resigned in August 1972, and the Library Board chose Jessie Abele, a Library Board member, to be the new Librarian. Mrs. Abele was unable to start work right away because of surgery, so board members filled in at the library. Mrs. Peterson and Library Assistant Edith Breifogle quickly set to work improving the comfort level of the library by hanging pictures and installing “two drop cords [extension cords?] and bulbs to improve the lighting.” It is noted in the minutes that the drop cords are safe for light only, not appliances. Older buildings like Cady Hall typically only had electrical wiring in the ceiling. Vacuum cleaners were not foreseen in 1912!

A discussion by the board about delinquent books reveals that Mr. Taylor must have left the shelves in some disarray. Mrs. Noble suggests that they be put in order before overdue notices go out “since some of the delinquent books have been found on the shelves.” Mrs. Noble also suggests the library’s first amnesty day.

It is at this time that the Patagonia Public Library begins receiving visiting professional librarians from the Arizona State Library System’s Library Extension Service. Materials published by the Arizona Department of Library, Archives and Public Records from this period reveal that as a state-wide agency, it was in the process of identifying the needs of Arizona’s public libraries and determining standards of service. These librarians provided both the Patagonia Public Library’s Board of Trustees and its staff with much-needed advice on cataloging, collection development, library management and grant writing. Mrs. Abele was also encouraged to attend workshops on subjects such as library assistance to Mexican-American children. By 1976, with the help, prodding, inspiration and advice of Extension Service librarians, the library had culled over 34 shelves of books, started the first catalog of the collection, identified subject areas which needed development (the juvenile and southwest collections), and begun an effective grant-writing campaign.

Despite President Nixon’s attempts to end federal funding for libraries, Federal Revenue Sharing funds become a consistent source of library income for Patagonia throughout the 1970s. In some years, this revenue sharing money comprises half the library’s budget. Federal bi-centennial Heritage funds granted in 1976 allowed the library to expand to a third “apartment,” which was furnished as the library’s first children’s room.

These efforts bore sweet fruit: between 1972 and 1980, library hours steadily increase to nearly 20 hours a week, and circulation grows five-fold. In its first 20 years, the Patagonia Public Library went from a project sponsored by energetic townswomen to a valued asset of the community. Problems with the facility, collection and community outreach remained; these would be addressed by future town librarians, and the good will & leadership of the library’s board and patrons.